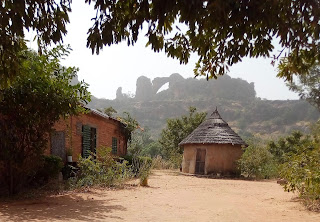

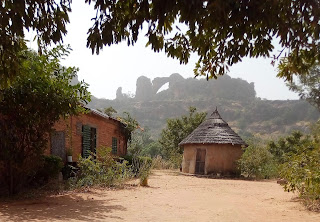

The road stretched ahead, marvelously empty of the city traffic. Trees, tall grasses, and startling rock formations met the eye in all directions. In the hazy distance, an archway appeared on the horizon.

|

| Malian countryside |

|

I missed the most interesting geological formations, but the

colorful plateaus were also a pleasure |

|

|

|

|

|

| Side country roads sprang up everywhere...inviting the curious |

This weekend gave me the first chance to get out of Bamako....and it has happily also provided me with a chance to introduce you to my neighbor, Attie. Attie invited me to a little market town of

Siby, where she was hoping to stock up on some shea butter before returning home to Holland this Christmas season.

Attie is just one of several people from the Netherlands that I have met here in Bamako; it seems to be another of those interesting, and possibly slightly unknown, migration connections. There is a pocket of Dutch here in Mali, and West Africa in general, which should, perhaps, not be so surprising since the Dutch have a fairly prolific history of

migration and colonization. I distinctly remember learning about the Dutch East India Company in my upstate NY elementary school, likely only because we did a play about it. But they've had strong roots in Surinam, South Africa, and even the Gold Coast.

Attie is also Mbalia's pre-school teacher, our elementary art teacher and a kindred spirit. She's spent a lot of time in Africa, has a few multi-cultural children and knows her way around a market. She drove us down the Malian highway commenting on the amazing birds in the trees, the beautiful flowering buds and singing to classic blues and African greats. Her commentary was sprinkled with a mixture of euphemisms like "schips" and an out and out m-f@$%er every now and then. She is the best combination of all the titles she wears- pre-school teacher, art teacher, grandmother, strong single mother, bike rider, nature lover, wax print and bazin fabric appreciator, and aficionado of West African culture.

|

| Mbalia & Attie, in the shade of a mango tree |

We stopped just outside of town and had a snack in a field of mango trees. The

Arch of Kamandjan could be seen in the distance and there was a constant, pleasant breeze. Many small groups passed us- groups of boys, women carrying their loads to the market, men on bikes, motorcyclists. Everyone waved hello and those on foot walked right up to greet us. Most of the kids offered a very proper, "Ou vas tu," which I kept hearing as "voiture." They weren't asking about our car but were wondering where we were going. I guess they were ready to serve as guides in case we needed. Or maybe they wanted a piece of our orange.

Some of the kids just stood there forming a little circle with us for what seemed like a long time. They never asked for anything directly and their intention wasn't quite clear. Curiosity? Hunger? One group of boys watched us taking pictures under the mango and "warned us" of a serpent in there. Attie has been in Mali for a good number of years and can remember "before the crisis" when tourists were abundant. She attributes the friendly and bold nature of people here to their familiarity with tourists from around the world. And of course their

generous, joking nature which is a pleasure to be on the receiving end of. (With my best theater face, I put on my courage and looked deep into the tree branches for that snake. Luckily, he wasn't anywhere I could see.)

After our snack, we set off across the plains to take a walk toward the arch. The Arch of Kamandjan holds an important place in Malian history and warrior legend. The fields just below are said to have been the battlegrounds where

Sundiata earned his title as King of the Malian Empire. Apparently you can (or could?) rent bicycles and take a tour, although the road gets very steep and is better served by hiking. We passed several motorcycles and an occasional biker or two, presumably on their way to or from the market. Attie and I both agreed it would be an interesting journey, on another day.

|

Some passing boys warned (or teased us) about

a serpent in the tree. Later evidence suggested

maybe there was something to it after all. |

|

| Mango love everywhere |

|

Freedom! No worries about getting

creamed by a motorcycle |

|

|

| The famous arch |

|

| Very sweet broken down house- with real doors in place! |

|

The doors had beautiful carvings and seemed

in remarkable condition. While I've seen them

in plenty of artist markets, I've never actually

seen them

in place on a house before. |

|

| We got closer to the arch, but it didn't get any clearer. Heavy haze. |

|

| Fresh snake skin just hanging from the tree. |

|

Mbalia drawing circles in the

sand around Miss Attie |

We walked until we ran across this restaurant. As is typical, gems like these are often described as "the French guy's place," although said French guy might not necessarily be on the premises anymore. True to Attie's nature, she saw the open gates and a truck in the drive and said, "Come on man, let's check it out." So we made our way down the dusty drive, marveling at the sweet breeze and relaxing nature of the space.

|

| Restaurant advertising on the road to the arch |

Someone came out to greet us and offer a drink. He moved a small table into the shade, set out some chairs and viola, restaurant open. While we were enjoying a beverage, a few other women came along, two on a bike and one older lady on a motorcycle. They all sat together and enjoyed a meal. It seemed like perhaps they were staying there, or had been frequent visitors.

You can rent a small round room for 6,000FCFA per person per night. I could definitely imagine bringing a book, some pencils and maybe some writing gear. What an extremely relaxing and beautiful scene to wake up to. (I did not see a hammock however, the only improvement I could really think of. The couple running the place were super nice, the breeze was constant and the air cool.)

|

| I imagine this would be a beautiful morning or sunset view |

|

| Our little table under the shade of the mango |

|

| Covered eating area |

|

| Solar panels, because, yes. |

|

Looking down this well gave me a

terrible

vertige- deep and dark. And of course

Attie had a

fantastically bizarre story

to share about a friend and a horse

who fell into a well together...... |

|

Hand washing system. This version included:

water

in the teapot, strainer cover over the

bowl, and

a place for holding soap. Super

effective and much "classier" than just the

bowl and the pot. It works easiest with two

people, like most systems in Africa. |

|

| This round hut can be rented for 6000FCFA a night (per person) |

After our drink, we made our way back to the car, again passing groups of women and children. One particular group of women were so enamored with Mbalia they walked right up to her and formed a circle around her, asking questions and saying hello. It would have been intimidating for a grown person, let alone a 3 year old, but she handled it mostly well. While she didn't exactly greet everyone in the traditional method, she did make it clear she wasn't a baby when someone suggested as much (as in cute baby. Not a baby, she insisted. Earlier she'd also refused to be called a princess, firmly reiterating her recent claim to be a dinosaur. She relegated Miss Attie to the status of princess and took a lot of pictures of "the princess and the dinosaur.")

|

| The princess and the dinosaur- grinning to the left. |

There was only one group of older boys that was somewhat bothersome, insisting Mbalia should hand over her Spiderman sunglasses. By this point, I was carrying her on my back and she was feeling sleepy. There was no way she was going to stand for a bit of teasing, and definitely not about the "Fiyah man's." She loves those things.

But we did pass another group of sweet boys, the smallest getting a ride in a push cart from his older brother. They exchanged greetings and when Attie turned the infamous, "Ou vas tu?" question on them, the oldest insisted he wasn't French. So they switched over to Bambara for the standard exchange. He had a winning smile and we had a chance to see it again as we drove away, waving goodbyes to all the women and children we passed. Toubabi is the general term they call out for foreigners and there was plenty of that being shouted after us as well.

We passed through a typical African market in our search for the shea butter that had inspired the trip. It was a bit more spacious and there were considerably less flies than the Bamako markets. The smells of fish powders and smooth nut butters filled the air.

Our ride back to the city was unremarkable if pleasant. We did catch a glimpse of a monkey crossing the road. He was as beige as the tall grass and we might have missed him but for Attie's vigilance with all things natural. I noticed a number of boys riding on the outside of the sotramas, Mali's version of the African vans that shuttle people from place to place. Every country does it slightly differently and here the seats go around the inside, with everyone sitting looking in at each other. A campfire circle without the campfire.

On the main roadway, the vans are just as often packed with people as they are overflowing with goods. In addition to being piled high on top with extra baggage, each van had at least one boy riding on the back, his feet perched on the bumper, holding onto the rails on top and one hand looped through a window or grasping the door edge. Some of them faced out, backs resting on the doors, gazing at the landscape as it passed and others clung precariously to the van with an eye facing the road ahead. One boy in particular had a melancholy look on his face. He held loosely onto a back door ladder, head leaning on his arm. Behind him were white doors painted with a Che Guevera portrait.

It was a deeply poetic image, but my phone had long since lost the battery and something about snapping his photo would have surely marred the moment. We gave him a thumbs up for encouragement as we passed and he returned the gesture with a tired smile.

Another van had 3 boys on the back, one perched up on top of the baggage. We passed him further down the road only to find he had descended from his vantage point and was holding on to the edges like the other guys. It seemed like a long, hard, and dangerous journey to Bamako. There can be no getting tired on the way.

I was extremely tired on the return trip and could barely keep my eyes open. All the fumes and dirt of the day had left me with a massive headache. Mbalia, a robust airplane traveler, fared less well in the car and eventually passed out herself.

In all, it was a tranquil day, calm and peaceful. Worth a return trip to Mande country.